Entono el mea culpa: me encanta In Sub/urbia de los Pet Shop Boys. De adolescente no solo tarareaba la letra, ¡incluso la cantaba! No tenía mucho secreto: recuerdo que en Holanda había una revista musical semanal que llevaba las letras en inglés de esa y otras muchas canciones. Lo divertido es que solo hace unos meses me percaté del comienzo de la canción: Suburbia/Where the suburbs met utopia… (¡Y cada vez que suena la palabra utopía, querido lector, me tengo que cuadrar!)

En esas andaba yo enfangado en el Renacimiento italiano y sus dos siglos de extraordinario poderío artístico. ¿Por qué Italia y no Francia o España? Según Jacob Burckhardt, Fernand Braudel y Michael Baxandall, la cultura de las ciudades-estado como Florencia o Venecia era muy superior al poseer una avanzada y sofisticada cultura material donde reinaba la nueva economía del dinero, lo que incentivaría el coleccionismo de las nuevas burguesías mercantiles urbanas.

Full disclosure: I love In Suburbia by Pet Shop Boys. As a teenager I used to sing it to myself, even out loud! The funny thing now is that it was not until some months ago that I noticed the beginning of the song: Suburbia/Where the suburbs met utopia… (And every time I hear the word utopia, my dear reader, I can’t but stand up and render the military salute!)

Back then I was fully immersed in the Italian Renaissance and its two extraordinary centuries of overwhelming artistic predomiance. But why Italy and not France or Spain? According to Jacob Burckhardt, Fernand Braudel and Michael Baxandall, the culture of city-states like Florence and Venice was far superior as it boasted an advanced and sophisticated material culture where the new economy of money reigned, stimulating the collecting habits of the new urban mercantile classes.

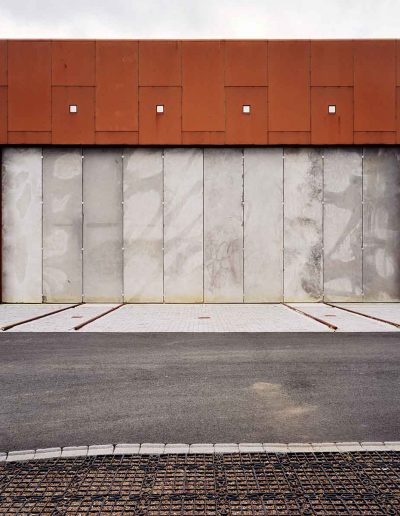

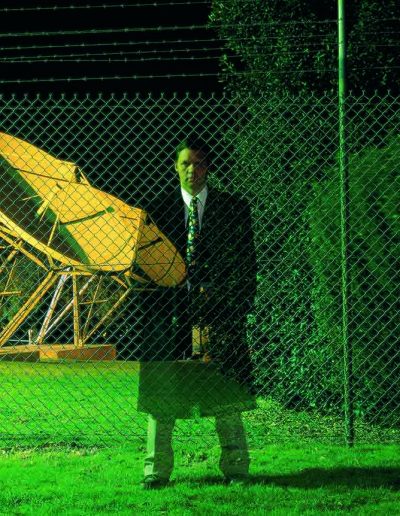

Untitled III – (Pumping Station). Serie Focal Points, 2006

Impresión de tinta de pigmentos sobre papel Hahnemüle

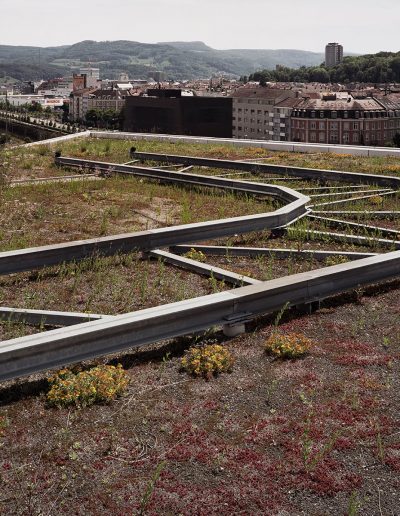

Brad Temkin, The Rouge (looking Southwest), Dearborn, MI, 2011

Impresión de tintas de carbón / Archival inkjet print

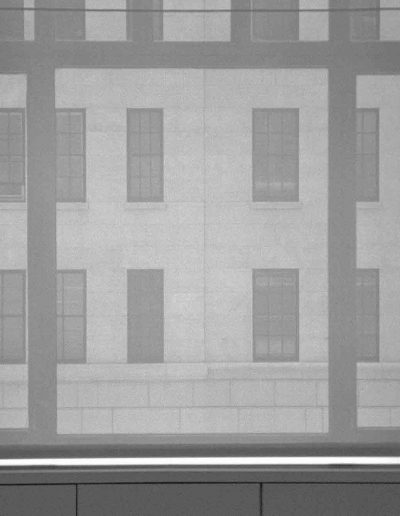

Brad Temkin, 111 South Wacker Drive (looking North) – Chicago, IL, 2010

Impresión de tintas de carbón / Archival inkjet print

Brad Temkin, Jacob Buckhardt Haus (looking East) – Basel, Switzerland, 2014

Impresión de tintas de carbón / Archival inkjet print

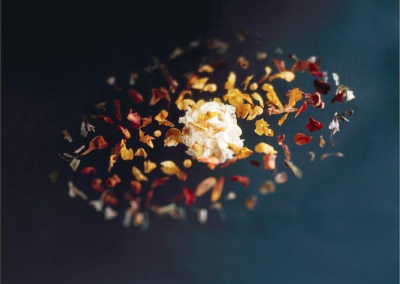

Iñigo Lasheras, Beyond a Certain Critical Mass #1, 2022

Impresión de tintas de pigmentos / Inkjet print

Y si mezclamos la ciudad renacentista con el concepto de “global city” de la socióloga neerlandesa Saskia Sassen —mientras suena el pegadizo estribillo de Pet Shop Boys de fondo—, entonces la narrativa de la urbe y el suburbio, en tanto que espacios avanzados que definen el destino del sujeto contemporáneo en el siglo XXI, tiene afilado encanto. Hay cierto sentido holístico: ¡del advenimiento de la ciudad renacentista desembocamos en las smart cities de hoy!

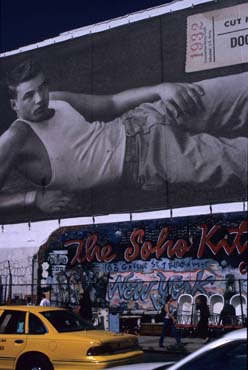

Suburbia/Where the suburbs met utopia—y de repente me pregunto: ¿la ciudad sigue siendo ese lugar de promisión y de esperanza? ¿Qué pasó con el suburbio y sus áreas residenciales donde huyeron las afortunadas clases medias para evitar el tráfico, el crimen o la contaminación del downtown? ¿La ciudad o los suburbios aún representan la materialización de aquella utopía sesentera?

And if we mix the Renaissance city with the concept of ‘global city’ coined by Dutch sociologist Saskia Sassen—while the catchy Pet Shop Boys chorus resonates in the background—then the narrative of urbia and suburbia, as privileged spaces that define the fate of the contemporary subject in the 21st-century, acquires cutting charm. We even find a certain holistic sense to it: from the advent of the Renaissance city we ended up in today’s smart cities!

Suburbia/Where the suburbs met utopia—and suddenly I find myself wondering: is the city still that place of promise and hope? What happened to the suburbs and its residential areas where the well-off middle classes took their refuge in order to escape downtown’s traffic, crime and polution? Does the city or the suburbs still represent the materialization of the ‘60s utopia?

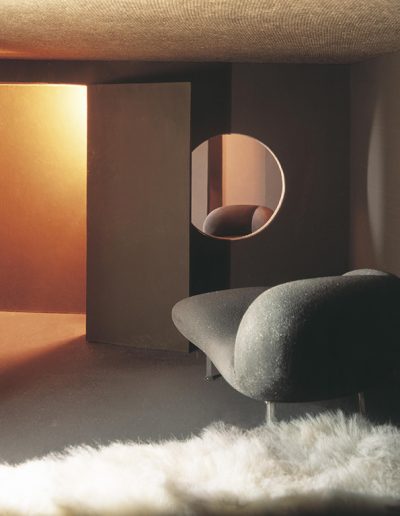

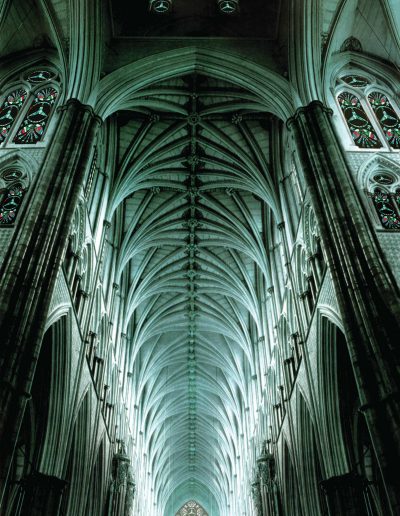

La exposición In Sub/urbia (O cuando el suburbio se rebela contra la utopía) reúne un grupo de destacados artistas (inter)nacionales que arrojan visiones fotográficas entre críticas, poéticas u oníricas sobre diferentes tipologías urbanas: desde espacios interiores de aires intimistas y pictóricos (Alexandra Ranner, José Manuel Ballester), pasando por espacios de culto como la iglesia (Darren Siwes, Chus García-Fraile), anodinas urbanizaciones de playa (Sergio Belinchón), insospechados parkings y puentes (Igor Mishiev, Aitor Ortiz), andamios y azoteas (Martin Liebscher, Brad Temkin), hangares de la NASA (Rosemary Laing) o asépticos no-lugares (Íñigo Lasheras).

La exposición In Sub/urbia supone al mismo tiempo una investigación sobre las diferentes estéticas y lenguajes fotográficos que abarcan la fotografía escenificada (Laing), la fotografía manipulada con Photoshop (García-Fraile, Mishiev, Ballester, Ortiz), la documentalista-conceptual (Belinchón, Temkin, Lasheras) o aquella realizada a partir de maquetas (Ranner) o que surge de la manipulación del tiempo de exposición (Siwes, Liebscher).

Y a todo esto me sigo preguntando: ¿suburbia acaso acabó en los brazos de utopia?

The exhibition In Sub/urbia (Or when Suburbia crashed Utopia) brings together a group of esteemed inter/national artists whose photographic research of the different urban typologies offers critical, poetic and even oneiric visions: from the intimate and pictorial interior spaces by Alexandra Ranner and José Manuel Ballester to the spaces of cult by Darren Siwes and Chus García-Fraile; from Sergio Belinchón’s anodyne beach urbanizations to undreamt of parking garages and bridges by Igor Mishiev and Aitor Ortiz; and finally from Martin Liebscher and Brad Temkin’s scaffoldings and rooftop terraces, Rosemary Laing’s NASA hangars to the aseptic non-spaces by Íñigo Lasheras.

The exhibit In Sub/urbia proposes at the same time an investigation into the different photographic aesthetics and languages encompassing staged photography (Rosemary Laing), digitally manipulated photography (García-Fraile, Mishiev, Ballester, Ortiz), documentary photography with a conceptual bend (Belinchón, Temkin, Lasheras) and photos that are either the result of using small architectural models (Ranner) or subjected to the manipulation of exposure time (Siwes, Liebscher).

And yet I keep asking myself: has suburbia finally met utopia?

EXPOSICIÓN FONDO DE GALERÍA

PAISAJES ARTIFICIALES

BEATRIZ ROMERO · LOLA GUERRERA · LORETO DAUDÉN

Beatriz Romero

S/T. 2007

Fotografía a color. Papel Hahnemüle 310 grms. Montada sobre moldura de madera y metacrilato

S/T. 2007

Fotografía a color. Papel Hahnemüle 310 grms. Montada sobre moldura de madera y metacrilato